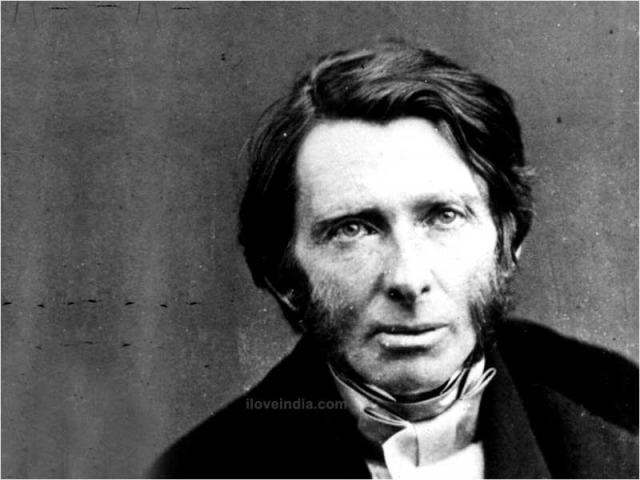

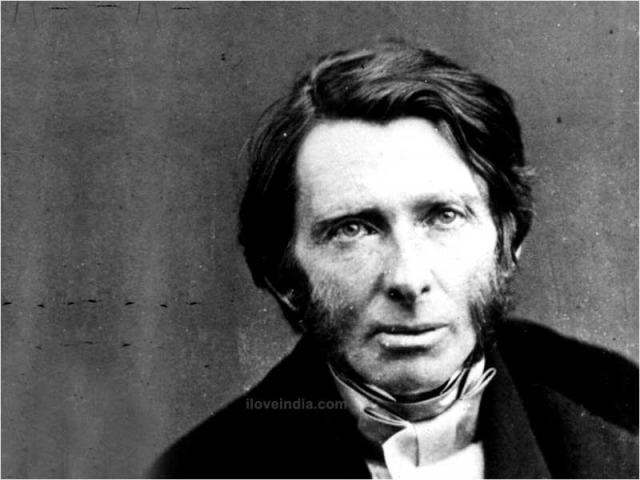

John Ruskin was arguably the most prominent cultural theorist of late Victorian and Edwardian ages. Read this short biography to know about him as his contributions.

John Ruskin Biography

Born On: February 8, 1819

Born In: London, England

Died On: January 20, 1900

Career: Artist, Poet, Art Critic, Social Thinker

Nationality: British

"One of those rare men who think with their heart” - this is how Leo Tolstoy described John Ruskin. Ruskin is a prominent English art critic, who through his ideas on naturalism in art immortalized himself as one of the greats of the Pax Britannica period (the period of Britain’s greatest imperial triumphs, during Queen Victoria’s rule). He was also a renowned poet and an artist himself. Though his paintings were never exhibited, his work was distinguished and classy. A controversial man by the virtue of his tastes, his ideas have influenced many including Gandhi, who translated his book “Unto this last” into Gujarati, naming it ‘Sarvodaya’. Oscar Wilde and Marcel Proust are some of the people who were deeply influenced by the works of this sage writer. Colleges, universities and lots of scholastic groups have been named after this prolific writer. Ruskin is one of pioneers of Christian socialism, though marred by allegations of pedophilia. In his lifetime, he had written over 250 works, which started from art history, but expanded to cover numerous topics which include science, geology, literary criticism, the environmental effects of pollution and mythology. Browse through the life of John Ruskin and know more about this great social thinker, whose ideas were well ahead of his times.

Early Life

Born in London, John Ruskin spent his childhood in South London. His father was a wine importer. Ruskin was home schooled for most part of his early years. Later, he enrolled himself at King's College, London and then Christ Church, Oxford. His studies were erratic, with his attendance being inconsistent. However, despite this, Ruskin impressed everyone after winning the Newdigate Prize for poetry. His peers were stirred, which led to him being awarded an honorary fourth-class degree, though he was seriously ill and was unable to attend college.

At the age of fifteen, Ruskin had already begun writing a series of articles for Loudon’s “Magazine of Natural History”. In 1836, his series “The Poetry of Architecture” started appearing in Loudon's “Architectural Magazine”. He wrote this under the assumed identity of "Kata Phusin”, which was a Greek term meaning “according to nature”. In this series, Ruskin reviewed countless buildings and argued that the buildings should match their natural surroundings and local materials must be utilized. In 1839, he published, “Transactions of the Meteorological Society”, which reflected his remarks on the then state of meteorological science.

Modern Painters Vs Ancient Greats

In 1843, Ruskin published the first volume of “Modern Painters “, a book which brought him much controversy and fame. Following his own theory that art should be natural and real, Ruskin claimed that modern landscape painters and especially his friend J. M. W. Turner were far superior to the “Old Masters" of the post-Renaissance period, including Gaspar Poussin, Claude Lorrain, Salvator Rosa and even Michelangelo, whom he depicted as a corrupting influence on art. He wrote that these “Old Masters” had given art an imaginative touch rather than the natural features, which were visible in the paintings of new age painters like Turner and James Duffield Harding (who was also Ruskin’s art tutor). He did consider few renaissance masters like Titian and Dürer, true to nature.

In the second half of his book, Ruskin explained his observations of nature. The second volume of the book consisted of his ideas of symbolism in art. Ruskin then shifted attention to architecture, which led to the publication of the two books “The Seven Lamps of Architecture” and “The Stones of Venice”. Both the books portrayed his belief that architecture and morality went hand in hand, and that the ‘Decorated Gothic’ style was the highest form of architecture yet achieved. By that time, Ruskin had given up on his pseudo name and started writing in his own name. His books catapulted his position as he became the most famous cultural theorist of his day.

Marriage & Mid Life

In the year 1848, Ruskin married Effie Gray, for whom he had written the fantasy novelette “The King of the Golden River” in 1841. The marriage, however, was not a happy affair. Meanwhile, Ruskin became involved with ‘Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood’ in 1848, which was formed by John Everett Millais, William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. These artists were influenced by Ruskin’s ideas and received both financial and written support from him. Millais even traveled to Scotland with Ruskin and Effie to paint the latter’s portrait. It was there that Millais’s relationship with Effie grew deeper. Along with Ruskin's non-consummation; the affair between Effie and Millais drew the final curtains on Ruskin’s marriage in 1854. Millias later married Effie and left the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, even changing the style of his painting. Ruskin continued to support all artists who were associated with Pre-Raphaelite style. In the year 1858, he also opened the School of Art in Sidney Street, Cambridge. He also wrote regular reviews of the annual exhibitions at the Royal Academy, under the title “Academy Notes”. Ruskin was so prominent and hypercritical that many artists loathed him.

Later Life & Death

After the 1850s under the influence of his friend, Thomas Carlyle and his own spiritual thinking, Ruskin left art criticism and moved towards political commentary. His masterpiece in this genre is “Unto This Last”, published in the December of 1860. In this book, Ruskin built on his own theories of social justice, which are said to be influential in formation of Britain’s Labour Party and basis of Christian socialism. After his father’s death, Ruskin disowned most of his inheritance based on his own socialist principles. He founded a charitable trust “Guild of St George” in the 1870s, and endowed it with large sums of money and a remarkable art collection. He also supported and funded housing reforms campaign by Octavia Hill. Ruskin even wrote a series of letters named “Fors Clavigera” aimed at the working class men of England during the same time.

Apart from this, Ruskin taught at the Working Men’s College. He was also appointed as the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at Oxford. Such was his popularity that Ruskin had to lecture twice— once to his students and then to the public. During the time when he was at Oxford, Ruskin became friends with Lewis Carroll, the author of the famous children tale “Alice in Wonderland”. It was during these times that Ruskin became enthralled of Rose la Touché; an intensely religious girl. He first met Rose in 1858, when she was only ten years old. He proposed to her eight years later in 1866, but was finally rejected in 1872, three years prior to her death. In the course of these events, Ruskin was devastated and plunged into a state of despair and mental illness.

In 1878, Ruskin wrote a contemptuous review of paintings by James McNeill Whistler, exhibited at the Grosvenor Gallery. He accused Whistler of asking “two hundred guineas for throwing a pot of paint in the public's face", for the latter’s work “Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket”. Annoyed and fumed, Whistler pressed charged for libel against Ruskin, the case which the former eventually won. Though the monetary repercussions were not serious, Ruskin's reputation was completely discolored thereafter. His literary works became more irrelevant and he faded from the public memory, as Aesthetic movement and Impressionism took over modern art and world itself. Ruskin spent his last years of his life at house named Brantwood, located on the shores of Coniston Water, in the Lake District of England. The house has now been converted into a museum dedicated to Ruskin.

Selected Works

-

Poems (1835–1846)

-

The Poetry of Architecture: Cottage, Villa, etc.(1837–1838)

-

The King of the Golden River, or The Black Brothers (1841)

-

Modern Painters(Vol. 1- 9)(1853-1860)

-

Review of Lord Lindsay's "Sketches of the History of Christian Art" (1847)

-

The Seven Lamps of Architecture (1849)

-

Letters to the Times in Defense of Hunt and Millais (1851)

-

Architecture and Painting (1854)

-

The True and the Beautiful in Nature, Art, Morals and Religion (1858)

-

The Harbours of England (1856)

-

"A Joy Forever" and Its Price in the Market, or The Political Economy of Art (1857 / 1880)

-

The Elements of Drawing, in Three Letters to Beginners (1857)

-

"Unto This Last": Four Essays on the First Principles of Political Economy (1860)

-

Munera Pulveris: Essays on Political Economy (1862-1863 / 1872)

-

Cestus of Aglaia (1864)

-

Time and Tide by Weare and Tyne: Twenty-five Letters to a Working Man of Sunderland on the Laws of Work (1867)

-

The Flamboyant Architecture of the Somme (1869)

-

The Queen of the Air: Being a Study of the Greek Myths of Cloud and Storm (1869)

-

Verona and its Rivers (1870)

-

Fors Clavigera: Letters to the Workmen and Labourers of Great Britain( Vol. 1- 4)(1871-80)

-

Love's Meinie (1873)

-

Michaelmas Term, 1872

-

Mornings in Florence (1877)

-

Pearls for Young Ladies (1878)

-

Review of Paintings by James McNeill Whistler (1878)

-

Fiction, Fair and Foul (1880)

-

Deucalion: Collected Studies of the Lapse of Waves and Life of Stones (1883)

-

St Mark's Rest (1884)

-

The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century (1884)

-

Bible of Amiens (1885)

-

Proserpina: Studies of Wayside Flowers while the Air was Yet Pure among the Alps and in the Scotland and England Which My Father Knew (1886)

-

Praeterita: Outlines of Scenes and Thoughts Perhaps Worthy of Memory in My Past Life (1885–1889)

-

Cook & Wedderburn, The Works of John Ruskin, Allen 1903

See also

More from iloveindia.com

- Home Remedies | Ayurveda | Vastu | Yoga | Feng Shui | Tattoos | Fitness | Garden | Nutrition | Parenting | Bikes | Cars | Baby Care | Indian Weddings | Festivals | Party ideas | Horoscope 2015 | Pets | Finance | Figures of Speech | Hotels in India : Delhi | Hyderabad | Chennai | Mumbai | Kolkata | Bangalore | Ahmedabad | Jaipur

- Contact Us Careers Disclaimer Privacy Policy Advertise With Us Lifestyle Sitemap Copyright iloveindia.com. All Rights Reserved.